The 20th Century in British Columbia was full of many changes within the education system and its educators. Specifically, we see a shift throughout the 20th century in how the teaching profession is regarded. Near the beginning of the 20th-century adults interested in teaching had little to no experience of knowledge. Then as teaching became a more prominent and structured profession, the ministry of education required its educators to at least have some previous relevant teaching experience or to attend teaching training schools such as “Normal School” in Vancouver. Lastly at the mid to end of the 20th century to enter the teaching profession, adults would need a Bachelor’s degree and to enter a professional development program. Over the 20th century, one of the major progressions is the requirements to become an educator and how the profession is portrayed.

(Right Image): Multi-room School – Hammond Elementary School in 1934. (Maple Ridge Archives, 1934).

Another change that occurred in the Canadian education system during the 20th century is where educators taught. Specifically, schools at the beginning of the 20th century were small in number, availability, and size. Most teachers taught a few students in a small one-room schoolhouse with no indoor plumbing. As well, these early educators in British Columbia would teach to different aged children in this one small schoolhouse. But as time went on and the population started to grow the education system had to shift into bigger multi-room school houses to support their bigger student population. Near the mid 20th century most teachers were assigned to a specific grade and room within a larger school building. Not only did where educators taught change over the 20th century but also what they taught.

There were three major shifts in the curriculum during the 20th century including the modernization reform, progressive education movement, and the inclusive education shift. The first major shift in the 20th century was at the beginning known as the modernization reform and occurred from 1892-1920. The modernization reform in the Canadian educational system focused on creating a united curriculum across Canada that would help create future model citizens. Specifically, the curriculum at this time focused on “Traditional subjects such as English (literature and grammar), mathematics, learning Latin, and the learning of historical dates and geography”. And introduced new subjects of home economics (“domestic science”), agricultural studies, and physical education to the curriculum, but not with uniform success” (Robson, 2019). These subjects, traditional and new were chosen because the government believed it would provide its students with the necessary modern skills and experiences they would need to survive after school. Additionally, the government focused on these traditional and new subjects because they believed they would support the “Dominant Anglo-Saxon values and to keep the Canadian curriculum free of influence” (Robson, 2019). Thus at the beginning of the 20th century, the Canadian curriculum and modernized reforms were focused on providing students with useful day-to-day skills and knowledge. As well, the curriculum was designed by the government to try and create future model citizens while focusing on embedding in their Anglo-Saxon values.

(Right Image): Students at scrap metal drive -Laura Secord Elementary in 1940. (Vancouver Archives, 1940).

The next major shift in the curriculum would be the progressive education movement which would take place from 1938-1950. This major shift in the curriculum would be focused on providing students with experiential learning instead of fact-based learning. Some of the reforms that came from this shift included “Child-centred, activity-based, and the cross-curricular integration of subject such socials studies” (Robson, 2019). This movement away from traditional lectures and teaching methods marked a change in the way educators viewed their work. During this part of the 20th-century educators began to be more experimental in their lesson planning and activities. Many of them found ways to bring real-life issues, situations, and skills into the classroom so students would be able to connect what they were learning in class and apply it to a real-world context.

The last major shift in the curriculum of the 20th century occurred from 1960-1999, this shift has been referred to as the inclusive education shift. Due to the rapid globalization and interconnectedness of the world, the Canadian government felt pressure from its students and parents to have a more inclusive and diverse curriculum. For instance, students “Wanted more “practical” knowledge that also reflected a more diverse (non-British) population” (Robson, 2019). Not only students but in general Canadians in the late 20th century wanted to see more diverse and non-Anglo-Saxon beliefs, knowledge, and histories represented in their education system. No longer was the general public okay with a white-washed version of the education system, they wished to see a more multicultural, non-sexist, and non-racist education system and environment for the future leaders of tomorrow. Overall the “Classroom was viewed as an ideal place to cultivate their desired social changes.” (Robson, 2019).

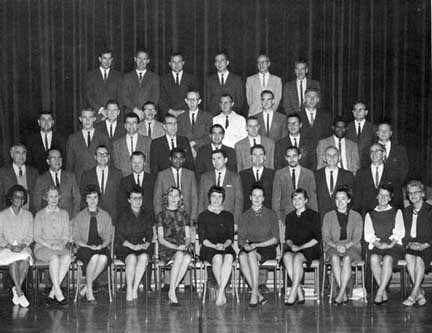

(Right Image): Staff photo at Simonds Elementary School – Langely in 1999. (LRTA, 1999).

Throughout the 20th century, the Canadian education system and its educators went through many changes. The schools, educators, and curriculum at the beginning of the 20th century looked drastically different when compared to the mid and end of the 20th century. But interestingly, although educators changed a lot within the 20th century many of them were remembered for similar reasons. Overall this has led me to believe that although the education system and professions have changed very much during the 20th century, teacher’s traits haven’t. In the local context of Mission, I have identified five educators with drastically different backgrounds, experiences, and styles. But all of them have been remembered for similar traits that made them successful in the field of education.